It’s about more than Turkey although this guy was cool to look at when he crossed my path

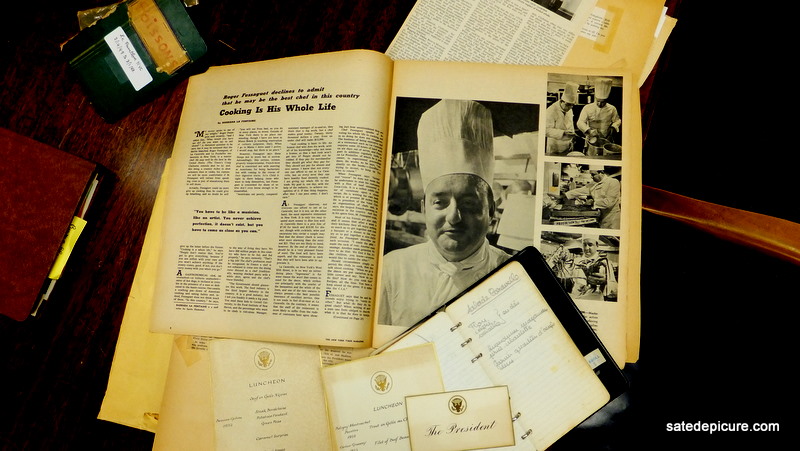

There are so many things in life to be thankful for but today I reflect on and give thanks to those professional Chefs from France who, starting in the mid-nineteenth century, paved the way for modern American gastronomy. My gratitude was triggered earlier this week when I spent time looking through the original reservation book from La Caravelle Restaurant formerly located in the Shoreham Hotel in New York City. La Caravelle operated from 1960 until 2004 but its greatest renown was during the tenure of Chef Roger Fessaguet from opening in 1960 until he retired in 1988. It was Fessaguet who meticulously preserved the reservation books, menus, recipe books and artifacts from La Caravelle that I so respectfully had the chance to hold and review. The first reservation book from La Caravelle is a hefty 10” x 18” with a hard green canvas cover. Inside, written by hand in red pencil on the top of the first page, is the date “September 21, 1960” with luncheon reservations written by hand in blue ink in the left column below and dinner reservations in the right column; some reservations having been highlighted in yellow. As I flip through the pages I notice that from the day the restaurant opened (a Wednesday night no less) Fessaguet didn’t close once until Thursday November 24th 1960 – Thanksgiving Day. He went 64 days without a rest, surely working fifteen hours a day (50+ covers at lunch, 80+ covers a dinner), every day for two months; a cool 105 hours per week. Fessaguet was a culinary athlete with an exceptional pedigree and conditioning for the time including more than a decade at the famed La Pavillon.

Chef Roger Fessaguet is last on the right, front row, seated at the table (Vatel Club of New York)

Most agree that the opening of Le Restaurant du Pavillon de France at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, a restaurant run by Maître d’ Henri Soulé and Chef Pierre Franey, marked the launch of fine dining in America. When World War II broke out in Europe Soule and Franey, in the U.S. for the fair at the time, remained in New York as refugees. On October 15, 1941 they opened La Pavillon as a permanent restaurant at 5 East 55th Street at Fifth Avenue. Within a few short years La Pavillon was recognized as the best restaurant in the country. Eight years later in 1949 Fessaguet arrived in the United States as a fresh seventeen year old from France via Liberty Ship and found his way from Baltimore, his place of disembarkment, to the kitchen of La Pavillon in New York. Fessaguet remained at La Pavillon from 1949 until 1960 except for a two year stint serving as a Marine in Korea.

Chef Fessaguet Portfolio (the card titled “The President” was left after a dinner by John F. Kennedy)

At twenty eight years of age he jumped at the opportunity to join Messieurs Fred Decré and Robert Meyzen, also from Le Pavillon to open La Caravelle. Decré and Meyzen chose the name La Caravelle, a wooden boat with three sails used in the 15th century to explore the world, to convey the idea of new promise, an idea fitting when you consider how Fessaguet arrived in the United States. La Carevelle was one of what would be several restaurants that were spawned from La Pavillon in the 1960’s and Fessaguet, Decré and Meyzen quickly rose in restaurant rankings nationally eventually becoming the favored restaurant of Ambassador Joseph Kennedy and his son President John F. Kennedy too. Within the first three weeks of opening Ambassador Kennedy’s name appears multiple times; he dined for five days in a row during October 1960. That Jackie Kennedy tapped Fessaguet to find a chef for the White House during Camelot isn’t surprising. Fessaguet initially offered the job to a young chef Jacques Pepin but Pepin chose another path and Rene Verdon ultimately received the nod.

La Caravelle Reservation Book, November 24th, 1960

(photo courtesy of Richard Gutman, Culinary Arts Museum, Johnson & Wales University)

So here I sit reflecting on contemporary American culinary culture, the influence of the San Sebastian set and Spanish culinary innovation (all that foaming and spherification), of the great chefs of Italy and the rising influence of Asian and Latin chefs. It seems that French chefs are no longer at the center of things today but their influence is so enduring. The culinary arts are headed to new levels in America and we owe a debt of gratitude to those early French Chefs who stormed our shores in the mid 20th century and remained. Within two generations of their arrival a whole new generation of American chefs were cultivated under their tutelage both here and back in France and those chefs (David Burke, Larry Forgione, Alfred Portale, Barry Wine etc.) took hold of the New York restaurant scene and never looked back. These are such wonderful shoulders to stand on; ones that we should remember, respect, and offer a nod of gratitude every once in a while. Heureux Thanksgiving mon ami.