It’s the end of May and I am on an airplane over the Atlantic Ocean at 33,000 feet sitting next to Chef Jacques Pepin. Through a series of interesting events, we are together in the third row of a three hour long Southwest airlines fligh. He’s on the aisle and I am at the window with an empty seat between us. Although I am trying to remain cool, my thoughts are percolating. To me, this is one of those once-in-a-lifetime situations that come along from time to time and I want to maximize the opportunity and ask him two or three good questions.

Along with memories of watching Julia Child’s WGBH Boston cooking show broadcast on my grandfather’s old black and white Philco television back in the early 1970’s, I remember Jacques as the first real French chef I ever saw. I have most of his cookbooks and have been a fan for decades. He’s 74 years old now and still going strong while aging gracefully. He is quite stylish in a dark blue blazer with light blue and lavender colored stripes, kaki pants, and trendy lavender colored shirt. His brown eyes are piercing with energy if not fading to grey a bit around the iris and he is sporting a neatly cropped grey beard and mustache. He still has long eyelashes and those same arched eyebrows that cause him to look like he is going to say something at any minute. His mind is sharper than ever and I am hoping he is willing to talk.

How often does a chef like me get three hours with a person like Jacques Pepin? What a privilege. I am nervous and sweaty. What will I ask him? I hope I don’t sound stupid. I can’t boil water compared to this guy. However, I do have some questions. What does all this recent “food-as-entertainment” mean to our profession? Where is the profession headed? “What makes a good chef good?” “What is the essence of a good chef?” “Is there a common set of competencies that all great chefs share?” In no way am I a student of Taylorism and scientific management, but I am drawn to breaking things down into their component parts as a way of making them easier to understand. Developing knowledge is easier when done in increments. There has to be a secret. What is the secret Jacques? Can such expertise be broken down into its component parts? I start by asking what makes a good chef good. It was a good question to ask!

Jacques weaves an answer to my questions into the 90 minute conversation we have in increments while flying north. “A good chef is true to himself. He knows his culinary soul and stays true to it. He doesn’t resist it; he builds on it and develops it.” He doesn’t over complicate it but instead climbs the mountain of culinary competency, becomes an expert, only to proceed back down the mountain to the place he started having made a full circle. The difference is, upon retuning to the base he is educated and competent, capable of many things but drawn to the basic and elegant cookery of his beginnings. His mastery has given way to elegant simplicity, elegant simplicity that only the highest degree of mastery would allow.

“A chef is as much a product of his upbringing and surroundings as the food he creates. Although he changes and evolves there is always a foundation within him laid in place during his youth.” Layers of food memories, food preferences, and food emotions are part of this foundation. To reject this foundation could be perilous. It could potentially cause a chef to become something he is not, although it is natural for a chef to expand beyond his origins, but only to a certain extent. The greatest chefs are the ones who climb the mountain to the summit, head back down and embrace the place where they started. They master culinary method and technique and understand their food foundation. Often, the combination of these two things is what defines the greatest chefs. Mastery paired with simplicity and a good dose of humility. Rather than try to cook what the people want for the simple sake of impressing them, it is better to cook what you love, what you keep in your culinary soul, to cook it perfectly, and to serve it because it represents who you are rather than to impress the eater. By default, the eater will be impressed because of the integrity and quality of your work. Chefs that make it full circle have established and embraced their culinary soul, developed their own identity, and found their own style and voice in the profession. After nearly 60 years in the profession, Pepin has the wisdom and experience from which to draw such an image. His message is profound.

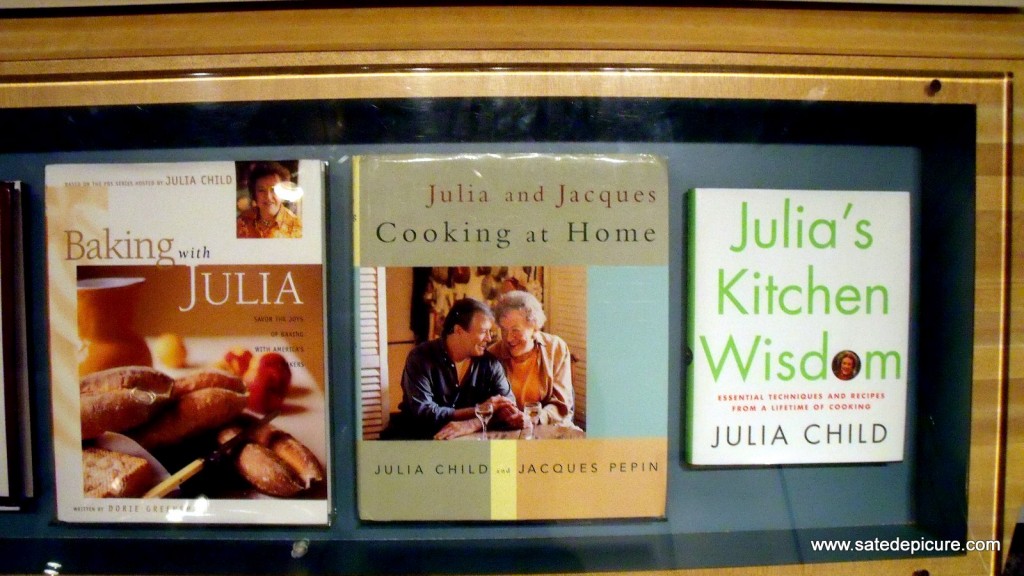

When asked about his most profound food memory he explained that he’s had so many that it is impossible to select just one. However, he does go on to tell me a story. When he was younger he spent hundreds of hours working with Julia Child in her kitchen at her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Over the years, the two filmed television shows, tested recipes for cookbooks, and cooked for pleasure there. Of the many chefs who worked with Julia, Jacques was second only to Julia and a few of her closest assistants in the amount of time spent in her kitchen. These facts are common knowledge in the food community, but what many people don’t know is that Jacques had one of the most profound moments in his life when he visited Julia Child’s kitchen at the Smithsonian Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. The experience was overwhelming for Jacques and he described is as “weird” and “unsettling” to see a place where he spent so much time preserved as a historic landmark. His description of the experience made clear that the contributions he and Julia made to the evolution of eating and cooking in American culture occurred by coincidence rather than by design. Seeing her kitchen encased in glass made clear to him in a flood of emotion the incredible extent of their contributions. His description of the experience caused him to well up with emotion and we fell silent in the moment.

While the emotions dissipate, we both enjoy some quiet time. Our plane is starting its descent now and I am frantically typing my scribbled notes into my laptop before the details of our conversation fade. He asks for my business card and offers to set up a visit to the French Culinary Institute sometime. I thank him for sharing his thoughts and wisdom and wish him well. I hope our next conversation will occur in a kitchen.